domenica 12 ottobre 2008

crunch crunch

Certo è che se gli stati immettono consistenti liquidità per salvare il sistema qualcosa se la prenderanno: fatte le debite proporzioni, chiedere che non tocchino nulla mi suona come la richiesta di un generale sconfitto di conservare lo status quo ante perchè cmq l'idea che lo muoveva era più giusta di quella dei suoi avversari. Per rimanere nella metafora bellica, esistono però paci giuste e paci inique, che sono notoriamente rischiose.

L'affossamento del mercato sarebbe sicuramente iniquo, oltre che stupido. Ma da ignorante chiedo agli "economisti", che immagino piuttosto affaccendati, se pensano abbia senso rispolverare l'idea di una tassa microscopica su tutte le transazioni (o magari solo su una parte) per costituire un grosso fondo di garanzia indipendente: quando ero ggggiovane si chiamava tobin tax e veniva immaginata per vari scopi, ora potrebbe forse essere uno delle clausole dell'armistizio tra Stato e mercato.

ps. non per menarmela, ma della clausola salva-manager, su cui si è fatto bello tremonti, avevo dato notizia il 9 settembre (qualche post in basso), quando era riferita solo ad alitalia. Giusto per dire che sembra strano che nessuno ne fosse a conoscenza

sabato 27 settembre 2008

BAILOUTS OR BAIL-INS

La mia impressione è che troppo spesso, sptutto in Italia, il fallimento (o meglio la possibilità di fallire) sia visto come cosa indegna e turpe, a cui persino si accompagna un sorta di giudizio morale implicito. "Ha fatto fallimento" tende a significare, da noi, "ha fatto cose sporche, è un ladro, un truffatore....". Ora, che talvolta ciò corrisponda alla verità dei fatti, non c'è dubbio, ma di qui a dire che un fallimento, per se stesso, ti catapulti immediatamente nella lega dei Coppola e Gnutti, ne corre, ne corre moltissimo. Forse è anche a causa di una storia nazionale in parte punteggiata da fallimenti cui si sono accompagnati scandali e illegalità di varia natura che il fallire continua a ricevere così cattiva stampa; tuttavia, io penso, il fallimento dovrebbe essere riabilitato. Tutti amiamo immaginare che il mondo che ci circonda sia molto più prevedibile di quanto la statistica ci dica, ma la realtà è che, ad esempio, di tutte le nuove imprese che nascono (di qualsiasi natura) ben oltre il 50% fallisce entro i primi cinque anni di vita. Pochi giorni fa, a Bruxelles, camminavo in centro con un amico il quale, nel vedere tutti i ristoranti pieni di gente ha detto "guarda che roba, basta aprire un ristorante e hai incassi assicurati". Quante volte abbiamo sentito un commento del genere? Io mille. Eppure, se vogliamo avere un'idea delle probabilità di successo nell'aprire un ristorante, non possiamo limitarci a contare chi ci è riuscito, perchè in tal modo mancano all'appello tutti quelli che ci hanno provato e hanno fallito, a causa della competizione, della sfiga, del ciclo economico..... Ragionare così falsa la nostra visione delle cose e ci porta ad addomesticare, impropriamente, la forza del caso. Fallire non soltanto è parte naturale delle cose, ma spesso è anche cosa desiderabile, perchè se nn si può fallire, difficilmente si può innovare. E non è certo proteggendo o salvando settori o società non più competitivi che si può arrivare lontano (l'industria automobilistica americana è probabilmene un caso di scuola, ma anche la ridente città di Asti, ove l'amministrazione comunale cerca di ostacolare in ogni modo la grande distribuzione per proteggere i piccoli, piccolissimi e microscopici esercenti, direi che non scherza!)

martedì 16 settembre 2008

Una simpatica clausola

Ringrazio ben per aver tenuto vivo il blog durante il nostro letargo estivo.

Dopo essere stato rapito tra lavoro e l'organizzazione della summer school del pd (che udite udite è stata una bella esperienza), vi inoltro questo posto preso da nfA

Alitalia: verso il fallimento della legalità

Roberto Bin

(9 settembre 2008)

“In relazione ai comportamenti, atti e provvedimenti che siano stati posti in essere dal 18 luglio 2007 fino alla data di entrata in vigore del presente decreto al fine di garantire la continuità aziendale di Alitalia-Linee aeree italiane S.p.A., nonché di Alitalia Servizi S.p.A. e delle società da queste controllate, in considerazione del preminente interesse pubblico alla necessità di assicurare il servizio pubblico di trasporto aereo passeggeri e merci in Italia, in particolare nei collegamenti con le aree

periferiche, la responsabilità per i relativi fatti commessi dagli amministratori, dai componenti del collegio sindacale, dal dirigente preposto alla redazione dei documenti contabili societari, è posta a carico esclusivamente delle predette società. Negli stessi limiti è esclusa la responsabilità amministrativa-contabile dei citati soggetti, dei pubblici dipendenti e dei soggetti comunque titolari di incarichi pubblici. Lo svolgimento di funzioni di amministrazione, direzione e controllo, nonché di sindaco o di dirigente preposto alla redazione dei documenti contabili societari nelle società indicate nel primo periodo non può costituire motivo per ritenere insussistente, in capo ai soggetti interessati, il possesso dei requisiti di professionalità richiesti per lo svolgimento delle predette funzioni in altre società.”

Questo non è uno scherzo, né il “caso” sottoposto da un collega fantasioso all’esercitazione degli studenti: è il testo dell’art. 3, comma 1, del decreto-legge 28 agosto 2008, n. 134, “Disposizioni urgenti in materia di ristrutturazione di grandi

imprese in crisi”. Il mio non vuole essere un commento, ma piuttosto una richiesta di aiuto: vorrei tanto che qualcuno mi spiegasse che cosa significa questa disposizione. Che l’Alitalia sia in condizioni gravissime lo sanno tutti; che il Governo se ne

preoccupi è – finalmente – una buona notizia. Ma il salvataggio dell’Alitalia – o meglio della parte “sana” di essa: dove andranno le sue amputazioni ormai necrotiche è un altro problema – può giustificare un provvedimento di “sanatoria” che mandi esenti da responsabilità amministratori, controllori, dirigenti, nonché “pubblici dipendenti”o “soggetti comunque titolari di incarichi pubblici” da “fatti commessi” e, in particolare, da irregolarità nella “redazione dei documenti contabili”?

A prima vista, per quanto riguarda i funzionari pubblici questa norma sembra cozzare con gli art. 28 e 103 Cost., che fissano il principio della responsabilità personale del pubblico funzionario: ma per la responsabilità degli amministratori di una società per azioni non c’è proprio alcuna “copertura” costituzionale? Che cosa vuol dire che la “responsabilità per i fatti commessi” è “posta a carico esclusivamente” della società? Di quale responsabilità si sta parlando? Fosse anche solo quella civile, l’azionista o il creditore perdono l’azione contro gli amministratori e possono agire solo contro la società, magari inciampando nel suo fallimento? È più che evidente che il decreto-legge incide nei rapporti tra privati, con effetti retroattivi, modificando i termini in cui si esercita il diritto di difesa e – c’è da supporre, perché non conosco la realtà processuale – interferendo nella funzione giurisdizionale, con buona pace di una bella serie di principi costituzionali, a partire da quello di eguaglianza per atterrare su quello di separazione dei poteri.

Insomma, il tenore di questa norma mi sembra incompatibile con i fondamenti primi dello Stato di diritto: qui si fa della ragion di stato (identificata nell’aver operato per la “continuità aziendale”) l’unica giustificazione di un provvedimento del tutto

abnorme. Si pensi infatti che, non solo coloro che hanno commesso dei “fatti” tutt’altro che commendevoli (dal punto di vista del rispetto delle regole vigenti, s’intende) sono mandati esenti da responsabilità personale, ma addirittura si vieta di considerarli per quello che sono: il fatto che abbiano falsificato i bilanci o commesso altri illeciti (a proposito, siamo forse difronte al primo caso di notitia criminis con forza di legge?) “non può costituire motivo per ritenere insussistente, in capo ai soggetti interessati, il possesso dei requisiti di professionalità richiesti per lo svolgimento delle predette

funzioni in altre società”. Fantastico! Si profila l’illegittimità delle delibere amministrative che motivassero la scelta comparativa di un dirigente sulla base dei trascorsi amministrativi in Alitalia dell’altro candidato? Oppure la denuncia per diffamazione del consigliere di amministrazione di una società privata che fa mettere a verbale il suo dissenso motivato (questo è il punto) rispetto alla nomina di uno dei nostri Alitalia boys? Qualcuno mi aiuta, per favore? Si, capisco, sono ipotesi paradossali, quasi fantascientifiche. Ma questa disposizione non lo è forse? Le leggi ad personam non sono una rarità nel nostro Paese, e non mi riferisco certo alla mitica “legge Bacchelli”. Ma ormai, come si vede, sta diventando un genere di massa. Poi andremo a spiegare agli immigrati clandestini il valore della legalità: non hanno mica da salvare la Compagnia di bandiera, loro; egoisticamente pensano a salvare solo se stessi.

martedì 26 agosto 2008

FORSE IN RUSSIA CI SONO PROBLEMI PIU' URGENTI DELLA GEORGIA.....

Sfogliando l'Economist mi hanno incuriosito alcune cifre riguardo la demografia russa e lo stato (del tutto pietoso) del suo sistema sanitario. Alcuni, come il demografo Murray Feshbach, propendono per proiezioni abbastanza estreme. Altri sono piu' cauti. Nondimeno, i dati relativi agli scorsi 15 anni sembrano parlare abbastanza chiaro e le cifre sulla crescente diffusione di HIV/AIDS, epatite e tubercolosi fanno in effetti una certa impressione (per l'OMS, tra il 45% ed il 55% delle prostitute di San Pietroburgo ha l'HIV. Dunque, watch out se siete nei paraggi!!)

Potrebbe essere interessante contrastare il caso russo con quello della Thailandia (che dalla prima meta' degli anni novanta in poi ha fatto della lotta all'AIDS un primario obiettivo, con estese campagne di prevenzione/informazione) e quello del Sud-Africa, ove sempre l'OMS ritiene che il 30% almeno delle donne gravide rechi il virus dell'HIV. Il Sud-Africa e' spesso citato come un paese che ha vissuto a lungo in uno stato di public denial del fenomeno (vedi la tardiva, malcerta confessione da parte di Mandela circa la morte del figlio a causa del virus), in tal modo ritardando ogni possibile misura correttiva. Per molti, la Russia assomiglia oggi piu' al Sud Africa che alla Thailandia. Naturalmente, molte di queste cifre si prestano a manipolazioni allegre, sptutto allorquando la Russia (ri)diventa bersaglio politico. Per esempio, nel 2007 pur continuando il trend di crescita negativa della popolazione, il decremento netto in Russia e' stato molto al di sotto della media dei precedenti 15 anni, situandosi attorno alle 280,000 unita' (fonte: Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, che e' in linea con i dati rilasciati dall'istituto russo di statistica e diffusi dal New York Times nell'aprile scorso. Inoltre: life expectancy maschile sotto i 60 anni e fertility rate a circa 1.35, ben sotto il replacement rate). Tuttavia, per l'Economist (la mia speculation e' che spesso le cifre vengono usate per fomentare l'ardore politico/retorico e nulla piu') sono invece state 800,000. Cio' non toglie che forse ci sarebbero temi piu' urgenti da affrontare per il well-being dei cittadini russi che non le enclavi caucasiche. In ogni caso, ecco un abstract sul tema:

Wilson Center Senior Scholar Murray Feshbach paints a dismal picture of health and population trends in Russia, even by his conservative estimates. By 2050, he predicts, Russia will lose at least a third of its current population. Disease, environmental hazards, and a decline in healthy newborns underlie this staggering statistic.

In Russia, deaths far outnumber births. Meanwhile, only a third of Russian babies are born healthy and last year's child health census showed that some 50 to 60 percent of all Russian children suffer from a chronic illness. Current mortality rates reflect the very high share of deaths between ages 20 and 49, potentially the most productive population segment. Such a population decline has a devastating impact on the labor force, military recruitment, and family formation.

By 2050, said Feshbach, Russia's current population of 144 million could fall to 101 million or as low as 77 million if factoring in the AIDS epidemic. Russia and Ukraine have the fastest growing rates of new HIV/AIDS cases in the world, reported Feshbach in his 2003 study, Russia's Health and Demographic Crises: Policy Implications and Consequences, published by the Chemical and Biological Arms Control Institute. If current trends continue, by 2020, 5-14 million Russians will be living with HIV and 250,000-650,000 will die from AIDS annually.

Other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) are propagating, as well, particularly syphilis. Initially spread through drug use and prostitution, STDs now are proliferating by heterosexual transmission. Another disease on the rise is tuberculosis (TB). In 2001, 781 Americans died from TB while Russia, with half America's population, had nearly 30,000 TB deaths. The same year, 18,000 Americans died from AIDS. Yet by 2010, at least four times that number will die from AIDS in Russia. Unfortunately, Russian government statistics remain optimistic, rather than realistic, diverting attention and funding from research and treatment.

Feshbach, an economist and demographer, has visited Moscow 53 times throughout his career. He worked in the Foreign Demographic Analysis Division of the U.S. Census Bureau for 25 years and later taught courses at Georgetown University on demography, health, and the environment in the Soviet Union for more than 20 years. Feshbach was a Wilson Center fellow during 1978-1979, after which he co-authored a 1980 report depicting the Soviet health crisis, exposing rising infant mortality and the negative impact of understated official statistics.

Economist Vladimir Treml of Duke University, in his 1999 book Censorship, Access, and Influence, wrote, "Several of my colleagues and I visiting Moscow in the early 1980s heard Soviet demographers and economists saying 'Feshbach saved thousands of infant lives in the Soviet Union,' implying that the Davis/Feshbach study was made available to high Soviet authorities, who directed certain (apparently beneficial) changes in public health policies."

Today, Feshbach continues his lifelong work to study the trends and impact of Russia's health and demographic crises. He is an investigator for a USAID project to track and analyze HIV/AIDS, TB, and other diseases in Russia and their impact on Russia's social transition.

Feshbach said, "I think the reason the Russians haven't paid attention [to this crisis], is that not enough people have died yet to capture their appropriate concern."

venerdì 15 agosto 2008

ROCKY MOUNTAIN INSTITUTE AND TED.COM

http://www.rmi.org/

http://www.ted.com/index.php/talks

Weight and Size Aren't the Same Thing

There was a time when light cars and small cars were believed to be one in the same. The reality is, it is size – not weight – that helps protect drivers from impact during a crash. It's also true that lightweight cars are less damaging to the environment because heavier cars burn more fuel and, therefore emit more carbon.Cars Have Bulked Up for Specific Reasons

According to the Rocky Mountain Institute, the average 2007 model SUV on average weighs 500 pounds more than in 1990, while compact cars have bulked up, too (about 374 pounds). And it's not because the size of vehicles has increased; instead, it's due to cars having bigger engines, heftier steel construction, and weightier parts. The reality is advancements in materials such as lightweight steel and aluminum have resulted in an ability to manufacture strong, stiff cars that are in line with steel construction without compromising safety (or size).Lightweighting Doesn't Mean Sacrificing Performance

Redesigning cars to make them more lightweight can be done in many ways, including making changes to the interiors of cars. For example, lighter seats add up to a lighter vehicle. At the end of the day, a lightweight car not only has superior handling, but it also accelerates faster and has the potential to brake quicker, too.It's Not Just the Body

There are many car parts that can benefit from the use of lightweight materials. These days, more and more new cars are being manufactured with aluminum components, such as engine covers, pumps, and cylinder blocks.Benefits of Being Light Weight

Using materials that reduce the weight of cars improves the efficiency of engines and gas mileage while decreasing petroleum usage and carbon dioxide emissions.giovedì 14 agosto 2008

"IT'S CHEAPER TO SAVE FUEL THAN TO BUY FUEL"

(http://postcarboncities.net/node/261), all'inizio ho incontrato un po' di persone del USGBC (http://postcarboncities.net/node/3287, e devo dire che Schwarzy appare essere particolarmente illuminato, tanto che ha fatto in teleconferenza il messaggio di apertura del convegno), che mi hanno introdotto anche alla business unit di GE Ecomagination (http://ge.ecomagination.com/

http://casa.quotidiano.net/

http://www.geotherm.it/esempi_

http://www.slideshare.net/

E' un esempio di una cosa assai interessante, credo. In ogni caso, me ne son venuto via da quei due giorni con due riflessioni principali:

1) Il dibattito dovrebbe concentrarsi assai meno sull'offerta di petrolio e molto piu' sul lato della domanda, perche' qui sono possibili enormi risparmi e recuperi di efficienza. A parte la quota edifici, il 70% del petrolio negli USA viene usato per il trasporto; di questo, circa la meta' e' utilizzato a livello cittadino per il viaggio di automobili da un punto A ad uno B. Prima di qualsiasi immaginifica soluzione, basta pensare a come il trasporto pubblico intelligente tipo Svezia possa creare massive economie di scala e poi guardare a come funziona, ad esempio, la Toyota Prius e paragonarla al tipico veicolo americano.

2) La legacy energetica dei paesi emergenti nn e' per nulla paragonabile a quella di Usa ed Europa, anzi, nn esiste legacy punto. Molti di essi hanno la possibilita' di diversificare le proprie fonti energetiche ab initio e lo stanno facendo. Infatti , mi ha sorpreso sapere chi e' l'uomo piu' ricco della Cina: tale, Shi Zhengrong, il fondatore della Suntech Power (all'inizio dell'espansione americana il piu' ricco era Rockfeller, un petroliere!!) (http://www.suntech-power.com)

Varie:

http://www.abengoasolar.com/sites/solar/en/

2) Siccome il dibattito e' in genere assai confuso, mi pare, ecco un documento della Sekab, azienda svedese che lavora all'etanolo di seconda generazione, ricavato dalla cellulosa e nn piu' dal mais.

http://www.sekab.com/Sve2/Informationssidor/Information%20PDF/Myths_vs_Facts.pdf

In ultimo, in chiave magari piu' futuristica e di curiosita', ecco un'elenco di cose gustose:

http://www.businessweek.com/

mercoledì 13 agosto 2008

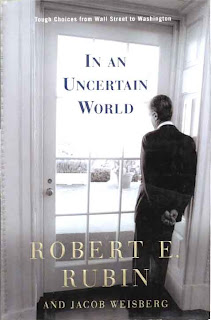

IN AN UNCERTAIN WORLD

Harvard Commencement Day Address

June 7th, 2001

Robert Rubin

Former Secretary of the Treasury of the United States

I am deeply honored to be your commencement speaker today. A little over forty years ago, I arrived as a freshman at Harvard College, from a public school in Miami Beach, Florida. I remember the first day of orientation, when the incoming freshman class met together at Memorial Hall, and the acting Dean of Freshman said, as an effort at reassurance, that only 2% of the incoming class would fail out. I felt that I was providing enormous protection to the rest of my incoming classmates, because in my mind I was going to fall short so colossally as to fill that whole 2% all by myself.

However, I remained, and my Harvard experience reshaped the intellectual framework through which I viewed everything that came my way, including the decision-making that has been the critical core of my professional life, both on Wall Street and in government. My views on that critical function of decision-making derived from my life's activities and formatively and powerfully from my Harvard experience, will be the primary focus of my remarks today, because I believe that decision-making will be at the core of your lives, too, no matter what you do. The only question will be how well you make those decisions.

Larry Summers, my former colleague at Treasury and your outstanding incoming President, used to say, when we faced tough situations in Washington, that life is about making choices. And I think that is exactly right. Curiously, though, despite this profoundly important reality, most people give very little serious consideration to how they make decisions. Thus, I would add to Larry's comment, that how thoughtfully you make those choices will critically affect how good those choices will be and how effective you will be.

In addition to discussing decision-making, I'll end my remarks by urging that today's graduates spend at least part of their careers in public service, where so many of our society's most complex decisions - affecting the lives of all of us - must be made.

Sophomore year, in Emerson Hall, I took Philosophy I with Professor Rafael Demos. I still remember the first day of class when a relatively short, white haired, elderly Greek man walked onto the stage in the lecture hall and instead of using a podium, turned a wastebasket upside down on a desk, put his notes on top, and started to speak. That unadorned simplicity - in the best sense - permeated his thinking and his teaching. And Philosophy I was only part of a broader Harvard intellectual experience that provided my most important training for subsequent careers in risk arbitrage investment on Wall Street and in economic policy making in government. Professor Demos would lead us through the great philosophical thinkers of the ages, not in the spirit of simply understanding and accepting their views, but rather to use their views as launching points for our own critical thinking, to question how well each thinker's analysis held together and, most importantly, to question how each assertion of truth was proven. And, as I slowly came to realize, the absolute truths that were asserted turned out to be unprovable and, in the final analysis, to be based on belief or assumption. Only later did I learn that many in modern science hold exactly the same view, that is that sophisticated theories can be developed and then proven by experimentation, but that ultimately this whole structure rests on unprovable assumptions.

I also remember that after we had struggled with thinkers whose work was immensely difficult to understand, Professor Demos then assigned another set of thinkers whose work was relatively easy to understand. However, we came to realize that this group lacked the trying but tight rigor and discipline of a Kant or Spinoza, and seemed intellectually loose, and unsatisfying. We then returned to the more difficult philosophers, with a newly developed appreciation for rigorous thinking.

From the guidance of this gentle professor, and from all my other experience at Harvard, I developed in the core of my being the view that there are no provable absolutes, and that, with the absence of provable certainty, all decisions are about probabilities - that is, all decisions are about the respective probabilities, of each of a number of possible outcomes actually occurring. Moreover, recognizing that all decisions are about probabilities rather than certainties should lead us to uncover and engage with the full array of complexities around making the best decisions.

Perhaps most importantly, rejecting the idea of certainties and needing to make the best judgments possible about probabilities, should drive you restlessly and rigorously to analyze and question whatever is before you - and to treat assertions as launching pads for analysis, not as accepted truths - in pursuit of better understanding.

Moreover, judging probabilities is far from the only complexity in decision-making. Often, each alternative possible outcome is not a simple, single effect, but the net effect of tradeoffs between competing considerations. I'm not expecting in these remarks to fully discuss these thoughts, but rather to convey my view as to the intellectual complexity inherent in making good decisions.

To exemplify both probabilities and tradeoffs, when the new administration's economic team opted for deficit reduction to stimulate economic recovery in 1993, we told the President that the likelihood of success was good, but that there were no guarantees, so that he could make a decision on this dramatic change in fiscal policy with full awareness of the economic and political risks. We also said that even if the strategy did work, the result would be a tradeoff between competing considerations - the positive of economic recovery and the negative of being unable to fund some of his desired programs. Again life is about making choices, and that quickly leads you to probabilities and tradeoffs.

With that, let me make one final point about how complex decision-making can be - the point that sometimes all choices are bad, but some are better than others. For example, our administration was greatly criticized for having worked with the International Monetary Fund to extend support to Russia in 1998, when Russia was facing a severe financial and economic crisis. Clearly, there was a substantial risk that additional assistance would not be effective. On the other hand, there was no question that our country had a very substantial national security interest in attempting to help stave off economic crisis in Russia, even if the likelihood of success was relatively low. All choices were probably bad in that case, including doing nothing, but there was still one choice that was least bad. Often, decision-makers faced with a situation where all choices are bad, react by not deciding. That, however, is a decision in itself, and often the wrong decision.

Let me mention one other situation that exemplifies what I've been saying about decision-making.

I often remember an experience early in my own Wall Street career, when I was investing our firm's capital in arbitrage and a friendly competitor at another firm explained his massive investment in what he viewed as a sure thing.

I agreed that it looked certain, but on the theory that there are no certainties but only probabilities, I made a very large investment, but still at a level where the loss was affordable if the entirely unexpected happened. And, it did. The investment failed: we took a large loss, and he took a loss beyond reason - and lost his job.

I doubt if Kant or Spinoza viewed themselves as offering the best and more important preparation for risk arbitrage or for intervention in the dollar/yen foreign exchange market or for the many other activities of a finance minister. But, in my view, they did. Looking back on all my years in the private and public sectors, in the most important issues, certainties were almost always illusory and misleading, as were the simple answers or opinions that often were the response to the complicated issues in both political discourse and the private sector. Reality is complex, and recognizing complexity and engaging with complexity was the path to best decision-making.

This, as you leave Harvard to undertake a vast variety of pursuits, I believe that nothing will be as important to you - no experience or professional training - as the ways of thinking and the restless pursuit of understanding you have had the opportunity to develop at this great institution.

An important corollary to recognizing that decisions are about probabilities is that decisions should not be judged by outcomes but by the quality of the decision-making, though outcomes are certainly one useful input in that evaluation.. Any individual decisions can be badly thought through, and yet be successful, or exceedingly well thought through, but be unsuccessful, because the recognized possibility of failure in fact occurs. But over time, more thoughtful decision-making will lead to better overall results, and more thoughtful decision-making can be encouraged by evaluating decisions on how well they were made rather than on outcome. In managing trading rooms, I always focused on evaluating and promoting traders not on their results alone, but also and very importantly, on the thinking that underlay their decisions. Unfortunately, this approach is not widely taken, much to the detriment of decision-making in both the private and public sectors.

In Washington, for example, there is very little tolerance for decisions that don't turn out to be successful, creating a tendency to counter productive risk aversion. In 1995, for example, our administration decided to assist Mexico financially in attempting recovery from an economic crisis, and the program succeeded. Then, three years later, we made a conceptually similar decision with regard to Russia and the effort did not succeed. I believe that the decision on Mexico would have been right even if the program had failed, and that the decision on Russia was right even though it did fail. In both cases, we knew that there were no guarantees of success - and in fact, real chances of failure. But we also felt that the chances of success were good enough, and the consequences of not engaging were a severe enough threat to American economic and national security interests, that involvement was the right decision. We were praised for the Mexican program, and criticized for the Russian program, in both cases because of the outcomes. I think both those reactions were based on looking at the wrong things. And that has real consequences. In the Mexican case, especially, President Clinton made the decision well knowing that failure could cause him great political damage, and that the judgment and evaluation of the decision in the media and the political universe would be based solely on the outcome. Fortunately, President Clinton was willing to take that risk, but too often this environment deters optimal decisions where there is a risk of failure.

And that leads me to the thoughts on public service I mentioned at the beginning of my remarks.

When I began in the new administration, a distinguished former cabinet member told me that I would now live off my previously accumulated intellectual capital, because I would be too busy to add to it.

I found just the opposite - that my time in government was an intense learning experience about how our government and our political processes worked and about a vast array of policy issues. I also found that the decisions that had to be made were often amongst the most complex faced anywhere in our society. Public service was a powerful challenge in using all the intellectual qualities that Harvard had sought to develop, towards the objective of furthering the public good.

I believe strongly in a market based, private sector driven economy. But there are a host of critically important functions that markets by their nature cannot or will not perform optimally, from education, programs for the inner city, law enforcement defense, and environmental protection or defense and foreign policy, and this array of functions becomes greater and more challenging in a world of increasing global interdependence.

Thus we must attract to government a critical mass of people with the intellectual drive, the restless quest for understanding, and the effectiveness at decision-making that we have been discussing this afternoon. There was a terrible period during my time in government when radio talk shows and even important elective officials regularly derogated public service and public servants. The atmosphere around government has substantially improved in the last few years, but simply reducing the level of disparagement is not enough. The people I worked with in government were as capable and committed as any I had worked with anywhere. But, to continue to attract the outstanding people to public service that the issues and functions require, I believe we all have the obligation - especially those who have received the benefits conferred by our great universities to reject the denigration of public service and to help re-establish an environment of honor and respect for public service and public servants.

None of this, let me quickly add, has anything to do with the perfectly proper debate about what the role of government should be in our society. This debate is as old as our republic, and the role of government has fluctuated substantially over the course of our history. However, what should not be a matter of debate - no matter what one views may be as to the appropriate role of government - is the respect that we accord public service and public servants.

Beyond urging that all of us contribute to re-establishing that environment of respect, I would also urge that those of you graduating today consider spending at least some time - and hopefully, for some of you, a whole career - in public service.

Public service, at whatever level of seniority, can provide immense challenge to all of your capabilities, as you help make and execute decisions in the most complex of circumstances, to further the well-being of the nation and even the world. And, you can get a very special insight into many of our society's most important policy issues, and a very special insight into how our society works - for example, how policy, politics, and media interact to affect what happens.

Government service, whether for a few years or for a career, can provide enormous challenge and intellectual growth, and the satisfaction of working to directly further the public good.

With that, let me conclude by thanking you for the opportunity to share views that I have thought a great deal about over the years. Important issues are complicated, and many of the most complicated are involved in the immense challenges requiring effective governance in our country and throughout the world.

You have been prepared by an outstanding institution - Harvard - to deal with this complexity in whatever you do and to contribute greatly to that governance.

Thus, you have an extraordinary opportunity to develop lives that work for you and to serve your country and all of human kind. That is a wonderful prospect.

And so, I congratulate each of you graduating today on all that you have accomplished and on this momentous occasion in your lives; I wish each of you the best in the years and decades ahead; and I hope you will cherish and advance in the world the great intellectual traditions that Harvard represents as so many of your predecessors have before you. Thank you.

A brief overview

The Halo Effect is an unusual business book: it offers a sharp critique of current management thinking, exposing many of the errors and mistaken ideas that pervade the business world, and suggests a more accurate way to think about company performance. I've tried to make it lively, informal, provocative, and accessible to a wide audience.

The main arguments of the book can be summarized in three points:

- Much of our thinking about company performance is shaped by the Halo Effect, which is tendency to make specific evaluations based on a general impression. When a company is growing and profitable, we tend to infer that it has a brilliant strategy, a visionary CEO, motivated people, and a vibrant culture. When performance falters, we’re quick to say the strategy was misguided, the CEO became arrogant, the people were complacent, and the culture stodgy. Using examples like Cisco, ABB, IBM, Lego, and more, I show how the Halo Effect is pervasive in the business world. At first, all of this may seem like harmless journalistic hyperbole, but when researchers gather data that are contaminated by the Halo Effect—including not only press accounts but interviews with managers—the findings are suspect. That is the principal flaw in the research of Jim Collins’s Good to Great, Collins and Porras’s Built to Last, and many other studies going back to Peters and Waterman’s In Search of Excellence. They claim to have identified the drivers of company performance, but have mainly shown the way that high performers are described. My book is the first to show why, for all their claims of voluminous data and rigorous analysis, their research is fundamentally flawed—and why their conclusions about the drivers of company performance are unfounded.

- Reliance on contaminated data leads to other errors, the most important of which is the widespread notion—explicit in Jim Collins’s work as well as that of many other management gurus—that companies can achieve success by following a formula. This is erroneous for a simple but profound reason: in business, performance is inherently relative, not absolute. I provide a very striking example about Kmart: on many objective dimensions (e.g., inventory management, procurement, logistics, automated reordering, etc.) Kmart improved during the 1990s. Why then did profits and market share continue to decline? Because on those very same measures, Wal-Mart and Target improved even more rapidly. Kmart’s failure was a relative failure, not an absolute one.

- Since performance is relative, not absolute, it follows that companies succeed when they do things differently than rivals, which means making choices under conditions of uncertainty, which in turn involves taking risks—and which may end in failure. The Halo Effect shifts our thinking about performance from one that looks for a formula for success, toward one that sees the world in terms of probabilities. Strategic leadership is about making choices, under uncertainty, that have the best chance to raise the probabilities of success, while never imagining that success can be predictably achieved. Even good decisions may lead to unfavorable outcomes, but that doesn’t mean the decision was wrong. The Halo Effect is not just an exercise in debunking flawed thinking—it seeks to improve the way that managers understand company performance and make strategic decisions.

Why I wrote The Halo Effect

I wrote The Halo Effect because during 25 years in and around the business world, I've seen so much nonsense—unsupported claims by famous gurus and self-described "thought leaders," sweeping assertions based on poor data, and simplistic stories that claim to be rigorous research. Worse, most people—including many very smart managers, consultants, and journalists— can't tell the difference between good and bad research. The Halo Effect is an attempt to raise the level of discussion in the business world, and to sharpen our skills of critical thinking about management.

"At a price, you can originate and sell anything", Settembre 2006

Nightmare Mortgages

They promise the American Dream: A home of your own -- with ultra-low rates and payments anyone can afford. Now, the trap has sprung

For cash-strapped homeowners, it was a pitch they couldn't refuse: Refinance your mortgage at a bargain rate and cut your payments in half. New home buyers, stretching to afford something in a super-heated market, didn't even need to produce documentation, much less a down payment.

Those who took the bait are in for a nasty surprise. While many Americans have started to worry about falling home prices, borrowers who jumped into so-called option ARM loans have another, more urgent problem: payments that are about to skyrocket.

The option adjustable rate mortgage (ARM) might be the riskiest and most complicated home loan product ever created. With its temptingly low minimum payments, the option ARM brought a whole new group of buyers into the housing market, extending the boom longer than it could have otherwise lasted, especially in the hottest markets. Suddenly, almost anyone could afford a home -- or so they thought. The option ARM's low payments are only temporary. And the less a borrower chooses to pay now, the more is tacked onto the balance.

The bill is coming due. Many of the option ARMs taken out in 2004 and 2005 are resetting at much higher payment schedules -- often to the astonishment of people who thought the low installments were fixed for at least five years. And because home prices have leveled off, borrowers can't count on rising equity to bail them out. What's more, steep penalties prevent them from refinancing. The most diligent home buyers asked enough questions to know that option ARMs can be fraught with risk. But others, caught up in real estate mania, ignored or failed to appreciate the risk.

There was plenty more going on behind the scenes they didn't know about, either: that their broker was paid more to sell option ARMs than other mortgages; that their lender is allowed to claim the full monthly payment as revenue on its books even when borrowers choose to pay much less; that the loan's interest rates and up-front fees might not have been set by their bank but rather by a hedge fund; and that they'll soon be confronted with the choice of coughing up higher payments or coughing up their home. The option ARM is "like the neutron bomb," says George McCarthy, a housing economist at

Because banks don't have to report how many option ARMs they underwrite, few choose to do so. But the best available estimates show that option ARMs have soared in popularity. They accounted for as little as 0.5% of all mortgages written in 2003, but that shot up to at least 12.3% through the first five months of this year, according to FirstAmerican LoanPerformance, an industry tracker. And while they made up at least 40% of mortgages in

The First Wave

After prolonging the boom, these exotic mortgages could worsen the bust. They also betray such a lack of due diligence on the part of lenders and borrowers that it raises questions of what other problems may be lurking. And most of the pain will be borne by ordinary people, not the lenders, brokers, or financiers who created the problem.

Gordon Burger is among the first wave of option ARM casualties. The 42-year-old police officer from a suburb of

After two months Burger noticed that the minimum payment of $1,697 was actually adding $1,000 to his balance every month. "I'm not making any ground on this house; it's a loss every month," he says. He says he was told by his lender, Minneapolis-based Homecoming Financial, a unit of Residential Capital, the nation's fifth-largest mortgage shop, that he'd have to pay more than $10,000 in prepayment penalties to refinance out of the loan. If he's unhappy, he should take it up with his broker, the bank said. "They know they're selling crap, and they're doing it in a way that's very deceiving," he says. "Unfortunately, I got sucked into it." In a written statement, Residential said it couldn't comment on Burger's loan but that "each mortgage is designed to meet the specific financial needs of a consumer."

The loans certainly meet the needs of banks. Option ARMs offer several payment choices each month. Among Burger's alternatives were one for $2,524, about what a standard fixed-rate mortgage would be on the new amount, and the $1,697 he pays. Why would his bank make the minimum so low? Thanks to a perfectly legal accounting practice, no matter how little Burger pays each month, the bank gets to record the full amount.

Option ARMs were created in 1981 and for years were marketed to well-heeled home buyers who wanted the option of making low payments most months and then paying off a big chunk all at once. For them, option ARMs offered flexibility.

So how did these unusual loans get into the hands of so many ordinary folks? The sequence of events was orderly and even rational, at least within a flawed system. In the early years of the housing boom, falling interest rates made safe fixed-rate loans attractive to borrowers. As home prices soared, banks pushed adjustable-rate loans with lower initial payments. When those got too pricey, banks hawked loans that required only interest payments for the first few years. And then they flogged option ARMs -- not as financial-planning tools for the wealthy but as affordability tools for the masses. Banks tapped an army of unregulated mortgage brokers to do what needed to be done to keep the money flowing, even if it meant putting dangerous loans in the hands of people who couldn't handle or didn't understand the risk. And Wall Street greased the skids by taking on much of the new risk banks were creating.

Now the signs of excess are crystal clear. Up to 80% of all option ARM borrowers make only the minimum payment each month, according to Fitch Ratings. The rest of the money gets added to the balance of the mortgage, a situation known as negative amortization. And once balances grow to a certain amount, the loans automatically reset at far higher payments. Most of these borrowers aren't paying down their loans; they're underpaying them up.

Yet the banking system has insulated itself reasonably well from the thousands of personal catastrophes to come. For one thing, banks can sell some of their option ARMs off to Wall Street, where they're packaged with other, better loans and re-sold in chunks to investors. Some $182 billion of the option ARMs written in 2004 and 2005 and an additional $83 billion this year have been sold, repackaged, rated by debt-rating agencies, and marketed to investors as mortgage-backed securities, says Bear, Stearns & Co. (BSC )Banks also sell an unknown amount of them directly to hedge funds and other big investors with appetites for risk.

The rest of the option ARMs remain on lenders' books, where for now they're generating huge phantom profits for some lenders. That's because, according to generally accepted accounting principles, or GAAP, banks can count as revenue the highest amount of an option ARM payment -- the so-called fully amortized amount -- even when borrowers make only the minimum payment. In other words, banks can claim future revenue now, inflating earnings per share.

For many industries, so-called accrual accounting, which lets companies book sales when they contract for them rather than when they receive the cash, makes sense. The revenues will eventually come. But accrual accounting doesn't apply well to option ARMs, since it's more difficult to know if unpaid interest will ever cross a banker's desk. "This is basically an IOU that may never get paid," says Robert Lacoursiere, an analyst at Banc of America Securities. James Grant of Grant's Interest Rate Observer recently wrote that negative-amortization accounting is "frankly a fraudulent gambit. But what it lacks in morality, it compensates for in ingenuity." The Financial Accounting Standards Board, which is responsible for keeping GAAP up to date, stands by its standard but told BusinessWeek in a written statement that it is "concerned that the disclosures associated with these types of loans [are] not providing enough transparency relative to their associated risks."

Camouflaged Losses

Risks or not, the accounting treatment is boosting reported profits sharply. At

In the middle of one of the hottest

Even the loans that blow up can be hidden with fancy bookkeeping. David Hendler of New York-based CreditSights, a bond research shop, predicts that banks in coming quarters will increasingly move weak loans into so-called held-for-sale accounts. There the loans will sit, sequestered from the rest of the portfolio, until they're sold to collection agencies or to investors. In the latter case, a transaction on an ailing loan registers on the books as a trading loss, gets mixed up with other trading activities and -- presto! -- it vanishes from shareholders' sight. "There are a lot of ways to camouflage the actual experience," says Hendler.

There's no way to camouflage what Harold, a former computer technician who asked BusinessWeek not to publish his last name, is about to face. He's disabled and has one source of income: the $1,600 per month he receives in Social Security disability payments. In September, 2005, Harold refinanced out of a fixed-rate mortgage and into an option ARM for his $150,000 home in

Hard Sell

To get the deals done, banks have turned increasingly to unregulated mortgage brokers, who now account for 80% of all mortgage originations, double what it was 10 years ago, according to the National Association of Mortgage Brokers. In 2004 banks began offering fatter sales commissions on option ARMs to encourage brokers to push them, says Gail McKenzie, assistant

The problem, of course, is that many brokers care more about commissions than customers. They use aggressive sales tactics, harping on the minimum payment on an option ARM and neglecting to mention the future implications. Some even imply verbally that temporary teaser rates of 1% to 2% are permanent, even though the fine print says otherwise. It's easy to confuse borrowers with option ARM numbers. A recent Federal Reserve study showed that one in four homeowners is mystified by basic adjustable-rate loans. Add multiple payment options into the mix, and the mortgage game can be utterly baffling.

Billy and Carolyn Shaw are among the growing ranks of borrowers who have taken out loans they say they didn't understand. The retired couple from the

Then there's the illegal stuff. Mortgage fraud is one of the fastest-growing white-collar crimes in the nation, costing $1 billion in 2005, double the year before. A slower housing market could foster more wrongdoing. "With a tighter market, you are going to find there is more incentive to manipulate," says Tim Irvin of Irvin Investigations & Research Services in Spring,

Concerns like these haven't curbed Wall Street's hunger for option ARMS. "At a price, you can originate or sell anything," says Thomas F. Marano, global head of mortgage and asset-backed securities at Bear Stearns. Hedge funds have been particularly active, buying risky loans directly from banks and cutting out the bundlers in the middle. Kathleen C. Engel, an associate professor of law at Cleveland-Marshall College of Law at

Pros Go Unscathed

Why are hedge funds willing to buy risky loans directly? Because they can demand terms that help insulate them from losses. And banks, knowing what the hedge funds want in advance, simply take it out of the hides of borrowers, many of whom qualify for lower rates based on their credit histories. "Even if the loan goes bad, [the hedge funds are] still making money hand over fist," says Engel.

Eventually, some of it will go sour. But the Wall Street pros who buy option ARMs are in the business of managing risk, and no one expects widespread losses. They've taken on billons in iffy option ARMs, but the loans are no shakier than the billions in emerging market debt or derivatives they buy and sell all the time. Blowups are factored into the investing decision.

Banks that hold lots of option ARMs on their books will surely be hit by loan defaults in coming years. "It's certainly reasonable to expect to see some excesses wrung out," says Brad A. Morrice, president and CEO of New Century Financial Corp. But even here the damage will likely be limited. Banks use insurance and other financial instruments to protect their portfolios, and they hold real assets -- homes -- as collateral. Christopher L. Cagan, director of research and analytics at First American Real Estate Solutions, a researcher and unit of title insurer First American, forecasts total defaults of $300 billion across all types of loans, not just option ARMs, over the next five years -- less than 1% of total homeowner equity. (In comparison, JPMorgan Chase & Co. alone has a mortgage portfolio of $182.8 billion.) Cagan estimates that banks will end up losing only $100 billion of it all told.

Most of the pain will be born by ordinary people. And it's already happening. More than a fifth of option ARM loans in 2004 and 2005 are upside down -- meaning borrowers' homes are worth less than their debt. If home prices fall 10%, that number would double. "The number of houses for sale is tripling in some markets, so people are not going to get out of their debt," says the Ford Foundation's McCarthy. "A lot are going to walk."

Jennifer and Eric Hinz of

Stories like these can be found across the socioeconomic spectrum, says Allen J. Fishbein, director of Housing & Credit Policy for the Consumer Federation of America. In a May focus group, the CFA found that option ARM customers at all income levels said the loans were the only way they could afford their homes. While many recognized that their mortgages could increase, "they professed complete surprise that they could increase as much as they could," says Fishbein. That lack of diligence will cost them over time.

Not that all option ARM holders go in blindly. While the loans are marketed aggressively, plenty of holders know exactly what they're getting into. Jon and Meghan Bachman of

So far they have stayed out of the fire. The couple, who are in their 30s, bought their first home, a 100-year-old farm house in Portland, Ore., in October, 2005, with a no-money-down loan for $200,000 from GreenPoint Mortgage, a unit of NorthFork Bancorporation Inc. By May, the value of the house had soared to $275,000. Rather than sit tight as their grandparents might have, the Bachmans, with an annual household income of $70,000, took out a home equity loan to put a $30,000 downpayment on an investment property in an up-and-coming neighborhood nearby. They pay a minimum of just $825 on their new $191,000 mortgage, and rent the house out for $100 more than that. Sooner or later, the payment will rise. Then they'll have to raise the rent to stay in the black. If the still-strong

Public policy has yet to catch up with the new complexities of the lending industry. Comptroller of the Currency John C. Dugan, the banking industry's main regulator, wants banks to clean up their act. A source inside the federal Office of the Comptroller says Dugan intends to raise lending standards, as he did last year on credit cards, where super-low minimum payments made it improbable that cardholders would ever pay down debts. New guidelines are expected this fall.

Fair-housing pundits suggest that mortgage lenders follow the lead of the securities industry and require that mortgage borrowers be not only eligible for a product but also suitable -- meaning the loan won't impose hardship. Says Consumer Federation of America's Fishbein: Buyers have to have a "reasonable prospect of being able to handle the payments, not at the initial rate, but [assuming] the worst-case scenario."

So far, banks have shown little desire to raise their standards. In February, Golden West announced it would raise its minimum option ARM payment to 2.6% of the loan. In March, Golden West's Sandler wrote a nine-page letter to the Office of Thrift Supervision decrying the lax lending standards he was seeing. "Foolish lenders who eventually stumble under the weight of their missteps will bring down innocent borrowers with them and leave the rest of us to clean up the mess," he wrote. But on May 7, Golden West announced it was selling out to Charlotte (N.C.)-based Wachovia Corp. (WB ). By June it had dropped its option ARM rate back down to 1.50%. Sandler says the rates were changed according to the bank's interest rate outlook.

Analyst Frederick Cannon of Keefe Bruyette & Woods says most banks don't apologize for their option ARM businesses. "Almost without exception everyone says [the option ARM] is a great loan, it's plenty regulated, and don't bug us," he says. In an April letter to regulators, Cindy Manzettie, chief credit officer for Fifth Third Bank in Cincinnati, said it's not the "lender's responsibility to help the consumer determine the appropriate payment option each month.... Paternalistic regulations that underestimate the intelligence of the American public do not work."

martedì 8 luglio 2008

strade vecchie e strade nuove

rispondo nella convinzione, già espressa altrove, che la questione sollevata in realtà non sia formulata in termini corretti e, così com’è formulata, investa una molteplicità di questioni, tutte complesse e diverse tra loro, che occorre quindi distinguere. Ci provo.

A mio avviso, la questione non è tanto l’astratta legittimità del principio di autodeterminazione nazionale quale criterio fondativo delle entità statuali (salvo ammettere tutta una serie di eccezioni laddove i rapporti di forza non consentano l’esplicazione di questo principio), quanto la comprensione storica dei molteplici e complessi significati della costruzione degli Stati nazionali e del nazionalismo in Europa e le loro implicazioni politiche attuali. In via preliminare, ritengo che la filosofia politica non offra l’approccio adeguato alla comprensione della questione in tutta la sua complessità, che è anzitutto complessità storica, ossia necessità di articolare una questione specifica in diversi contesti storici. Di qui la perplessità sul tipo di classificazione – a mio avviso astratta e semplificante – che è proposta: in particolare il punto 2 mi sembra fonte di ambiguità irrisolte e al contempo cruciali per la nostra questione.

Il punto 1 esprime una posizione cosmopolita discendente dalla cultura illuminista che non può che rappresentare un ideale regolativo per il singolo individuo. Questa posizione, in generale, mi pare l’unica accettabile da un punto di vista etico per il singolo individuo: tuttavia, essendo fondata sul primato della cultura individuale, costituisce non un diritto, ma un privilegio (in questo senso, non democratico). In realtà, credo che sia più legittimo, per noi, definirci europei che cittadini del mondo: infatti, rispetto al mondo degli illuministi, il nostro mondo è diventato ben più vasto e articolato. Definirsi europei, dal mio punto di vista, non significa costruire una identità astratta e omogenea, statica ed esclusiva, ma riconoscere la varietà e la complessità della storia europea, che racchiude identità molteplici e stratificate, contraddittorie e relazionali (e spesso conflittuali): questo riconoscimento, che è la condizione di possibilità per un confronto con l’altro, che non si traduca in negazione di sé, è il fondamento di quella forma di etnocentrismo critico già teorizzata da Ernesto De Martino.

Il punto 3, invece, esprime la posizione classica del diritto internazionale, fondamento della Carta dell’Onu, per cui la forza politica che controlla il territorio di uno Stato va intesa come il rappresentante legittimo di quello Stato, a patto che ne garantisca sovranità e indipendenza. Oltre a questo principio (politico e non giuridico) che consente il riconoscimento dei governi esistenti, sovrani e indipendenti, la carta dell’Onu sancisce il principio di autodeterminazione dei popoli, fin dall’art. 1, par. 2. Tuttavia, sul concetto di popolo e sui suoi criteri di definizione (ad es. interno ed esterno), sulle condizioni di realizzabilità di questo principio ( possibilità di costituire uno stato sovrano e indipendente) e sui modi in cui interagisce con altri principi (come quello di integrità territoriale degli altri Stati) il dibattito tra i giuristi continua ad essere aperto e complesso: non ho però le competenze per seguirlo nel dettaglio.

Ora, torniamo, o meglio, avviciniamoci, invece, al punto 2. Che cosa si intende con quella che tu definisci “madrepatria”? Preliminare a questa discussione è anzitutto la distinzione teorica tra Stato moderno e Stato nazionale: nel caso dello Stato moderno, vale la definizione weberiana di potere fondato sulla rivendicazione del monopolio della violenza legittima; nel caso dello Stato nazionale, vale un principio di legittimità diverso e complementare al primo, che è l’aspirazione dello Stato a rappresentare la comunità nazionale e che si è tentato di realizzare (con esiti alterni e differenziati) attraverso gli strumenti della scuola pubblica (e, in una seconda fase, dei mezzi di comunicazione di massa come radio e televisione) e della coscrizione obbligatoria. Lo Stato moderno di diritto fonda una comunità di cittadini, che si riconoscono nella legge: da questo punto di vista, la cittadinanza è basata sul comune riconoscimento della legge, a prescindere dalle appartenenze etniche, religiose, culturali ecc… Lo Stato nazionale, che è organicamente legato al principio di sovranità popolare, invece pretende di fondare una comunità nazionale, che si immagina omogenea sotto il profilo etnico, religioso, culturale ecc. Mentre il primo concetto è inclusivo (è lo ius soli), il secondo è esclusivo (ius sanguinis). Tuttavia, tutto questo è vero soltanto dal punto di vista concettuale: infatti, gli Stati nazionali, nella loro concreta operatività storica, si sono mossi in forma contraddittoria, intrecciando i due concetti, nella definizione del criterio di cittadinanza. Questa è la contraddizione fondamentale e irrisolta di cui è stata matrice la Rivoluzione francese, racchiusa nella tensione tra la Dichiarazione universale dei diritti dell’uomo (con la conseguente aspirazione all’esportazione della democrazia) e la proclamazione del primo Stato nazionale (con la conseguente nascita del nazionalismo): su tutto questo Hannah Arendt ha scritto pagine insuperate.

Ora proviamo a mettere meglio a fuoco che cosa è la nazione, di cui si possono dare una definizione essenzialistica (o etnicista) o una definizione costruttivista (o culturalista). Quest’ultima posizione, o meglio l’insieme delle posizioni riconducibili a questa definizione, tende ormai ad essere dominante in sede storiografica (non di rado in forme estremiste, per cui la nazione si riduce ad una pura e semplice invenzione). A mio avviso, è storicamente fondata una posizione che sia in grado di conciliare l’elemento politico costruttivo (direi addirittura rivoluzionario) della nazione con le diversità sociali e culturali concretamente determinate (e, sia pur in misura variabile, preesistenti), su cui le élites politiche hanno lavorato per costituire nuovi Stati. I processi di costruzione dello Stato nazionale tra XIX e XX secolo sono stati quanto mai complessi e diversificati di contesto in contesto; sono stati condotti da élites politiche che hanno trovato nel vocabolario e nel progetto politico fondato sulla nazione un nuovo e potente principio di legittimazione; si sono svolti in contesti in cui il grado di omogeneità culturale, la natura delle istituzioni politiche preesistenti, lo stadio di sviluppo socio-economico erano altamente differenziati. E’ indubbio che la Francia è stata il laboratorio del primo vero e proprio Stato nazionale moderno: il suo esempio ha ispirato le élites politiche otto-novecentesche in tutta Europa. Tuttavia, l’esportazione o affermazione di questo modello politico, basato sull’aspirazione all’omogeneità culturale, nei territori imperiali plurilinguistici e multireligiosi dell’Europa centro-orientale, in particolare dopo la Prima guerra mondiale, generò una catena di tensioni destabilizzanti, che rappresentò un moltiplicatore dei conflitti, almeno fino alla fine della Seconda guerra mondiale. Non è possibile ovviamente ripercorrere nel dettaglio tutte quelle vicende, ma non si possono dimenticare per inquadrare quanto è avvenuto nell’ex-Jugoslavia negli anni Novanta.

Occorre, inoltre, tener presente che il senso di appartenenza nazionale in Europa occidentale ha subito profonde metamorfosi, a partire dal trauma della Seconda guerra mondiale. Il nazionalismo più aperto e aggressivo, che era stato identificato come l’origine delle esperienze fascista e nazista, fu ufficialmente bandito nel dopoguerra (per quanto sia sopravvissuto in forme meno palesi e più latenti). L’adesione emotiva alla nazione e il suo nesso organico con la coscrizione obbligatoria si sono progressivamente allentati, in un quadro se non di pace, di non guerra. Inoltre, lo Stato nazionale, perduta la volontà di essere strumento di espansione militare, è diventato erogatore di servizi e garanzie sociali che hanno costruito un nuovo senso di cittadinanza, non più basato sull’immagine (che risale alla rivoluzione francese) della nazione in armi: non a caso, l’attuale crisi della sovranità statuale è legata a doppio filo alla crisi del Welfare State. Infine, l’avvio e lo sviluppo del processo di integrazione europea ha aperto la strada ad una diversa possibilità di configurazione dei rapporti tra Stati in Europa, rispetto alla rivendicazione di una sovranità nazionale assoluta (nonostante le sue ostinate resistenze, che definiscono una nuova e più sottile forma di nazionalismo), e ad una nuova prospettiva di definizione di cittadinanza, concorrenziale rispetto a quella esclusivamente nazionale (su questa ad esempio si basa il trattato di Schengen).

La parola “Europa” ed il riferimento al processo di integrazione europea NON compaiono una volta nel tuo testo! E’ invece proprio questo nuovo livello del processo politico europeo che consente di individuare il carattere anacronistico delle politiche di carattere esclusivamente nazionale (ad esempio sull’immigrazione, questione che tenderà ad assumere un ruolo sempre più centrale nella società europea). Più in generale, il diritto all’autodeterminazione nazionale in Europa tende a farsi sempre più anacronistico, nel momento in cui è in corso un processo che, ancorché lento, faticoso e contraddittorio, tende a superare la sovranità nazionale stessa.

Indubbiamente, diverse sono state le traiettorie storiche dei paesi che si trovavano al di là della cortina di ferro. Concordo sul fatto che la soluzione ideale per l’ex-Jugoslavia (così come per l’Urss) sarebbe stata una forma di federazione democratica che conciliasse le esigenze dell’unità con il riconoscimento delle diversità, che contenesse le spinte disgregative e che impedisse tanto la diffusione dei nazionalismi quanto lo spargimento di sangue. In Urss, si è avuta la diffusione dei nazionalismi, ma non lo spargimento di sangue (salvo rare, ma significative eccezioni nel Caucaso, come il conflitto tra la Georgia e l’Abkhazia, quello tra Armenia e Azerbaigian per il Nagorno-Karabakh, la Cecenia): questo forse perché, come recita un vecchio adagio marxiano, la storia una prima volta è tragedia, una seconda volta è commedia e l’Urss la tragedia l’aveva già ben conosciuta. O, più precisamente, per una serie di ragioni storiche che non è questa l’occasione per ripercorrere, ma che vanno dal ruolo di Gorbacev e Eltsin alla volontà degli Stati Uniti di tenere sotto controllo una vasta area con un potenziale atomico devastante, fino alla possibilità di contenere su scala strettamente locale le conflittualità che emergevano dallo disfacimento dello Stato sovietico e delle sue strutture federali. Invece, l’ex-Jugoslavia ha conosciuto la tragedia, proprio nel senso di un viluppo tra contraddizioni insolubili che derivavano dalla crisi della Jugoslavia post-titina e che credo fossero difficilmente governabili fin dal 1991-92 sotto la spinta di nazionalismi sempre più violenti. La responsabilità nello scoppio del conflitto e nel suo proseguimento va attribuita, secondo me, principalmente alla Serbia di Milosevic. Tuttavia, non si può dimenticare la concorrente e concomitante spinta all’estremismo nazionalista da parte di tutti gli attori in campo (soprattutto da parte della Croazia). Inoltre, va tenuto presente che, sulla base di scelte più o meno deliberate, vi sono sempre aree geopolitiche che vengono a configurarsi come lungo di confronto e di contesa tra gli interessi delle grandi potenze: i Balcani negli anni Novanta sono stati anche il teatro di “una guerra civile larvata” in cui si misurarono i rapporti di forza internazionali (qualcosa di simile alla Spagna degli anni Trenta). Infine, occorre ricordare che la complessità di quelle guerre di successione alla Jugoslavia sta nella pluralità di tempi storici al loro interno compresenti, che ricapitolano fenomeni storici tipicamente ottocenteschi (guerre per l’indipendenza “nazionale”, ossia per la costruzione di nuovi Stati), novecenteschi (eredità dei conflitti ideologici della Seconda guerra mondiale) e post-novecenteschi (conflitti di “civiltà”, ossia di religione).

Sul Kosovo la mia posizione deriva conseguentemente dal discorso fin qui fatto. Credo che la sua dichiarazione di indipendenza sia illegittima dal punto di vista formale, controproducente dal punto di vista politico, ma purtroppo del tutto organica al processo storico nei Balcani (e altrove in Europa centro-orientale). Ribadisco che la soluzione ottimale passava attraverso la rinegoziazione del legame federale tra le Repubbliche, in un quadro di democratizzazione del sistema politico: tuttavia, varie forze e contingenze hanno portato ad un intreccio sempre più stretto tra democratizzazione ed etnicizzazione della politica jugoslava, tra 1990 e 1991. Questo non può far dimenticare che c’è una differenza fondamentale tra la Bosnia-Erzegovina e Kosovo: la Bosnia-Erzegovina era legittimata a organizzare un referendum per l’indipendenza (avvenuto nel febbraio 1992 e sostenuto da una vasta partecipazione: considero illegittime le obiezioni che muovono dal fatto che la comunità serba decise di astenersi, perché il voto democratico è individuale), secondo quanto prevedeva la Costituzione jugoslava del 1974, la quale riconosceva la possibilità di secessione per le singole Repubbliche. Al contrario, il Kosovo, che era un’unità amministrativa della Repubblica jugoslava di Serbia (una sua “provincia autonoma”), non aveva il diritto di proclamare la propria indipendenza. La guerra del 1999, che rispondeva all’interesse della Nato di allargare il proprio raggio d’azione verso Est, era stata fatta per arrestare la repressione serba in Kosovo, non per creare le condizioni per l’indipendenza del Kosovo. La sola via legale per l’indipendenza del Kosovo doveva passare attraverso un referendum, organizzato su tutto il territorio della Repubblica serba, Stato di cui fino al giorno della proclamazione di indipendenza unilaterale faceva parte: l’indipendenza del Kosovo, infatti, doveva costituire l’eventuale esito della consultazione popolare, non il suo presupposto. Forse non è male ribadire, in questa sede di discussione, che la democrazia (come argomenta Bobbio) non è il puro e semplice rispetto della volontà della maggioranza, ma anche la legalità delle procedure di formazione della stessa volontà democratica, l’indipendenza reciproca dei diversi poteri, la tutela dei diritti delle minoranze, la possibilità di formazione di una maggioranza alternativa con mezzi pacifici. La politica della maggioranza albanese del Kosovo ha contraddetto tutte queste norme democratiche fondamentali nei confronti della minoranza serba, dopo la guerra del 1999, sotto il protettorato NATO. Inoltre, gli albanesi del Kosovo sono una nazione che può rivendicare il principio di autodeterminazione, oppure, con la loro indipendenza, si è aperta soltanto la via per la loro annessione all’Albania? Infine, il Kosovo risponde a quei criteri di sovranità e indipendenza che, come si diceva più sopra, devono costituire il presupposto per il riconoscimento di uno Stato oppure si sono creati i presupposti per l’esistenza di una vasta area sottratta a qualunque controllo di legalità in cui possono proliferare le criminalità organizzate di tutto il mondo?

Non credo che il riconoscimento dell’indipendenza del Kosovo sia il modo efficace per garantire la stabilizzazione e la democratizzazione di tutta la regione; al contrario, l’Europa e gli Stati Uniti con il Kosovo hanno perso la possibilità di cominciare a invertire tendenze storiche profonde e di impostare su basi nuove, coerenti con il processo di integrazione europea, la politica nei Balcani. Molte altre cose si potrebbero e si potranno dire: a me basta aver restituito una dimensione storica minima alle questioni di cui si discute. In questo caso, chi conosca la strada vecchia, saprà che, con la nuova, peggio non potrà andare!